The Film Noir Odyssey

Writer: Bryant Ford and Paul Gangelin

Story: Philip MacDonald

Director: Anthony Mann

Cast: William Terry, Virginia Grey, Helene Thimig

Cinematography: Reggie Lanning

Score: Morton Scott

Studio: Republic Pictures

Release: September 12, 1944

Welcome to my new Film Noir Odyssey miniseries, this time focusing on the films of Anthony Mann. I’ve covered a few of his movies previously, mostly with middling reaction, with the exception of the exquisite “The Tall Target,” which is certainly the best noir Abraham Lincoln was ever involved in. My main takeaway from him so far is that his movies often look incredible, but really rise and fall on the strength of the screenplay. He’s not the type of director who can overcome a haphazard story with his visuals or crisp tone… which is fine. Most directors, many of whom have Oscars, fall into that camp.

Mann’s career can be broken into three very distinct phases: his early films noir, his Westerns (entirely unseen by me) and his late career big-budget epics (unfortunately mostly seen by me). Within his noir filmography, Mann is all but inseparable to critics from cinematographer John Alton, who defined many of Mann’s films just as much as he did. I’ll get into Alton more when we reach his collaborations with Mann.

But first, let’s discuss Mann’s first movie that at least comes close to the film noir genre: “Strangers in the Night.” This film is noir in the same way that Alfred Hitchcock’s seminal “Rebecca” is noir… in that it’s a blatant rip-off of that film but also that it’s more concerned about the gothic aspects of its story. Mann had already directed several features, and here was surrounded by a bunch of middle-of-the road collaborators – had it not had the Mann connection, I doubt this movie would be remembered at all.

Johnny (William Terry) is wounded in the war and, during his recuperation, becomes a pen-pal with the mysterious Rosemary, whose name and address he finds in a book he’s reading. He becomes emotionally attached to Rosemary, and after recovering heads to California to seek her out and tell her that he loves her. Concurrently, a doctor named Leslie (Virginia Grey) begins working in the same community. When Johnny arrives at the windswept, cliffside home where Rosemary apparently lives, he instead finds her eccentric mother Hilda (Helene Thimig) and Hilda’s also eccentric best friend Ivy (Edith Barrett), who keeps looking like she can end the movie by saying a single sentence, but then never quite doing it. Hilda says Rosemary is out of town for a few days and asks Johnny to stay with him, then conspicuously waves away any and all follow-up questions. Meanwhile, Johnny and Leslie begin to fall in love while trying to solve the question of where, exactly, is Rosemary.

“Strangers in the Night” came out four years after “Rebecca” won Best Picture and has many of the same bells and whistles that movie had. But the reason “Rebecca” remains a great film is because of its honest exploration of imposter syndrome, something just about every human on this planet has experienced many times. This movie has no interesting thematic subtext anywhere near that, and as a result the viewer just stares at the screen watching a soulless impersonation of a better story. The centerpiece scenes in both films feature a woman leading our hero through the missing woman’s bedroom, noting small things about that person’s life while underlining their obsession with what is gone but never forgotten. In “Rebecca” the scene is excruciating emotionally because we are with the main character every second. Here, Hilda may as well be a real estate agent.

The screen story is by crime author Philip MacDonald, and I’d love to get my hands on that original treatment because I have a feeling it’s a lot more interesting than the finished product. MacDonald wrote a few scripts, including Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto movies, but is primarily remembered for his novels, including “The Rasp” and the outstanding “Murder Gone Mad.” The screenplay, on the other hand, is written by Bryant Ford and Paul Gangelin… neither of whom had sterling careers. Despite massively overstuffing the first five minutes with about 40 minutes of material, once the first act ends the movie hinges on what Roger Ebert called “The Idiot Plot.”

What is The Idiot Plot, you ask? Well, if a single character says a single sentence (which she should logically say), then the movie is over. So instead, the audience is trapped while the filmmakers are stretching and stretching to try and keep the movie to a suitable running time (it’s only 56 minutes long) instead of just having the characters ask follow-up questions. Early in the film, the writers seem so intent on padding that they write in a grisly train accident (!!!) to avoid having Johnny ask Leslie: “Have you heard of Rosemary?”

And even after the big reveal that Hilda made up Rosemary (gasp!), Johnny and Leslie stick around for drinks and chit chat because the movie has only been on for 45 minutes! The lack of logic and pure idiocy of Hilda’s final attempt on the duo’s life makes the ending laughable way before a painting of “Rosemary” apparently becomes sentient and makes a suicide fall on Hilda. That is not an exaggeration.

The only actor who holds her own is Grey, who plays her doctor matter-of-factly throughout and remains firmly above the material. Meanwhile, Terry seems like a doofus in every scene and Thimig swallows all the nearby scenery. Reggie Lanning’s cinematography is undistinguished, making that windswept cliffside house look like a falling-apart standing set (which it probably was).

All of this is to say that Mann wasn’t surrounded by any diamonds in the rough, so I’m not sure how much of the blame I should place on him. “Strangers in the Night” is a bad movie, a worse “Rebecca” rip-off and honestly not worth all the words I have devoted to discussing it. Other critics have bent over backwards in order to find merit in it, but… why? Sometimes bad is just plain bad – I can only hope “The Great Flamarion” is going to be a step up from this dreck.

Score: *

The Film Noir Odyssey

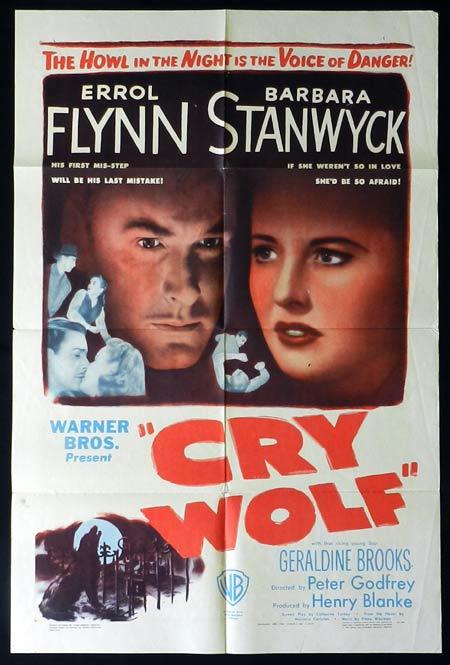

The Film Noir Odyssey I’m a sucker for this kind of noir… where it’s meshed together with old dark houses and vaguely romantic melodrama. Daphne du Marier didn’t write the novel upon which “Cry Wolf” was based, but she might as well have. What truly elevates this from most other entries in this sub-genre is Sandra (and Stanwyck’s performance). Girl is take-no-prisoners in the best way possible. “I am not a placid girl,” she says early in a great line of dialogue, and damn if she isn’t right. She uses a dumbwaiter to get into the hidden wing and, later, crawls across the roof to gain entry through a skylight. She slaps a motherfucker when he crosses a line. And she is blunt instead of hiding how she’s feeling. I genuinely loved her and was rooting for her hard to uncover the secret.

I’m a sucker for this kind of noir… where it’s meshed together with old dark houses and vaguely romantic melodrama. Daphne du Marier didn’t write the novel upon which “Cry Wolf” was based, but she might as well have. What truly elevates this from most other entries in this sub-genre is Sandra (and Stanwyck’s performance). Girl is take-no-prisoners in the best way possible. “I am not a placid girl,” she says early in a great line of dialogue, and damn if she isn’t right. She uses a dumbwaiter to get into the hidden wing and, later, crawls across the roof to gain entry through a skylight. She slaps a motherfucker when he crosses a line. And she is blunt instead of hiding how she’s feeling. I genuinely loved her and was rooting for her hard to uncover the secret. The twist certainly hasn’t aged well in terms of shaming those who have mental illness and calling them too fargone to ever find love, marry or have children. In other words, it’s gross as hell. But it’s also, well, the cheapest possible way out of the tantalizing maze the rest of the film has gotten the viewer lost in. It’s basically telling you that there isn’t even a maze. And those few lines of dialogue undo all the fine character work we’ve seen from Sandra… turns out she was just a silly woman after all who should have never questioned the man in charge.

The twist certainly hasn’t aged well in terms of shaming those who have mental illness and calling them too fargone to ever find love, marry or have children. In other words, it’s gross as hell. But it’s also, well, the cheapest possible way out of the tantalizing maze the rest of the film has gotten the viewer lost in. It’s basically telling you that there isn’t even a maze. And those few lines of dialogue undo all the fine character work we’ve seen from Sandra… turns out she was just a silly woman after all who should have never questioned the man in charge. The Film Noir Odyssey

The Film Noir Odyssey The film takes place in Malaya, and opens with Leslie unloading all the bullets in a gun into a family friend named Hammond. As one does. Leslie claims that Hammond just showed up and attempted to rape her, but still must stand trial for her act. Her husband Robert (Herbert Marshall) is endlessly supportive, but her lawyer Howard (James Stephenson) begins to have some suspicions. Then a note surfaces that Leslie sent to Hammond, inviting him to come over that night, and Howard finds himself in very, very grey ethical territory. The note is in the possession of Hammond’s wife (Gale Sondergaard in unfortunate yellow face), and she has some very specific demands before it’s turned over.

The film takes place in Malaya, and opens with Leslie unloading all the bullets in a gun into a family friend named Hammond. As one does. Leslie claims that Hammond just showed up and attempted to rape her, but still must stand trial for her act. Her husband Robert (Herbert Marshall) is endlessly supportive, but her lawyer Howard (James Stephenson) begins to have some suspicions. Then a note surfaces that Leslie sent to Hammond, inviting him to come over that night, and Howard finds himself in very, very grey ethical territory. The note is in the possession of Hammond’s wife (Gale Sondergaard in unfortunate yellow face), and she has some very specific demands before it’s turned over. These sequences make a great set-up for when Leslie’s true motives for the murder begin to present themselves and things get messy. Koch interestingly paints all of the British characters as somehow disconnected from reality, whereas all of the native characters have a full understanding of life. Aside from Leslie, the most fascinating character in the film is one of Howard’s assistants, a man named Ong Chi Seng. Played by Sen Yung (Charlie Chan’s Number Two Son represent!), Ong at first seems complacent, with a fake smile plastered on his face as he tries to accommodate everything Howard needs. But watch the way he brings up knowledge of the letter, and later the way he smiles at Howard when he proudly admits that he’s making $2,000 out of the letter/money exchange. It’s a small role, but Yung knocks it out of the park.

These sequences make a great set-up for when Leslie’s true motives for the murder begin to present themselves and things get messy. Koch interestingly paints all of the British characters as somehow disconnected from reality, whereas all of the native characters have a full understanding of life. Aside from Leslie, the most fascinating character in the film is one of Howard’s assistants, a man named Ong Chi Seng. Played by Sen Yung (Charlie Chan’s Number Two Son represent!), Ong at first seems complacent, with a fake smile plastered on his face as he tries to accommodate everything Howard needs. But watch the way he brings up knowledge of the letter, and later the way he smiles at Howard when he proudly admits that he’s making $2,000 out of the letter/money exchange. It’s a small role, but Yung knocks it out of the park. The Noir Odyssey

The Noir Odyssey Alone in the mansion, Agnes becomes obsessed with finding out what happened to Jennifer. Jim keeps telling her not to worry about it, which of course makes Agnes even more curious, and also suspicious of him – could he be the reason she is gone?

Alone in the mansion, Agnes becomes obsessed with finding out what happened to Jennifer. Jim keeps telling her not to worry about it, which of course makes Agnes even more curious, and also suspicious of him – could he be the reason she is gone? Lupino is all wrong for her part. While she’s played repressed wonderfully elsewhere, including the much-better gothic noir “Ladies in Retirement,” here her persona is too strong for Agnes. We sense an inherent strength in Lupino that makes Agnes’ weaknesses seem all the more silly. No one played this type of character better than Joan Fontaine (see “Rebecca” and “Suspicion”), and to imagine her in the role is to imagine a much better movie. Duff (who was then Lupino’s husband) doesn’t do much to soften Jim’s edges, making him seem almost bipolar in the way he focuses on caring for Agnes one moment and completely dismissing her the next. There’s one moment shared between the two actors in a record store that is elegantly staged and beautifully performed, but that’s the exception, not the rule.

Lupino is all wrong for her part. While she’s played repressed wonderfully elsewhere, including the much-better gothic noir “Ladies in Retirement,” here her persona is too strong for Agnes. We sense an inherent strength in Lupino that makes Agnes’ weaknesses seem all the more silly. No one played this type of character better than Joan Fontaine (see “Rebecca” and “Suspicion”), and to imagine her in the role is to imagine a much better movie. Duff (who was then Lupino’s husband) doesn’t do much to soften Jim’s edges, making him seem almost bipolar in the way he focuses on caring for Agnes one moment and completely dismissing her the next. There’s one moment shared between the two actors in a record store that is elegantly staged and beautifully performed, but that’s the exception, not the rule.