The Film Noir Odyssey

Writer: Edith Sommer

Adaptation: Charles Schnee

Additional Dialogue: Robert Soderberg and George Oppenheimer

Director: Nicholas Ray

Cast: Joan Fontaine, Robert Ryan, Zachary Scott, Joan Leslie, Mel Ferrer

Cinematography: Nicholas Musuraca

Music: Frederick Hollander

Studio: RKO

Release: July 15, 1950

Christabel Caine Carey has all the makings of a great femme fatale. First, there’s her name. She’s gorgeous, manipulative and knows how to get her claws deep in a number of men. After arriving in San Francisco, she is almost instantly seducing a rich man whose fiancé is giving Christabel free room and board, while also sleeping with a tortured artist on the side. But despite an awesome title, “Born to Be Bad” never quite takes Christabel into the “fatale” part of the name. She doesn’t stab anyone or throw someone downstairs… or even plant murder in the mind of her lover. What a shame.

That’s because “Born to Be Bad” isn’t really noir – it’s a melodrama that, like “Daisy Kenyon” or “Queen Bee,” many critics and historians lump into the genre because its creative team is a veritable murderer’s row of noir icons. Ray! Musuraca! Fontaine! Ryan! It sure feels like it should be noir, even though it isn’t. And yet, here we are.

Christabel is played by Joan Fontaine, and as the film opens, she moves to San Francisco to live with Donna (Joan Leslie), a book editor doing a favor for her boss and Christabel’s uncle John (Harold Vermilyea). Donna is engaged to the super rich Curtis (Zachary Scott), and soon Christabel is planting seeds to break the two apart and seduce Curtis. But Christabel also finds herself attracted to one of Donna’s writers Nick (Robert Ryan) in a totally carnal way. Also in play is artist Gobby (Mel Ferrer), who seems to be capable of seeing through Christabel’s sweet surface.

Screenwriter Edith Sommer (“The Best of Everything”) places all the pieces on the chessboard quite well, and her strength is in bringing depth to characters that would otherwise be bland ciphers. She also does backflips to try and stretch the narrative and make sure none of the ensemble seem stupid for believing Christabel for as long as they do, which is appreciated. In addition, she deserves a lot of credit for Gobby (despite that horrible name), who is clearly gay and treated as just another character instead of a walking cliché.

That said, she is obviously having the most fun with the Christabel and Nick pairing, which is toxic but impossible to look away from. The first time we meet Nick, he comes off like a complete asshole, but soon Christabel all but says “Hold my beer” and essentially becomes Satan. Sommer gives the best line to Nick: “I love you so much I wish I liked you!” It certainly helps that Fontaine and Ryan have off-the-charts chemistry with one another – both when they spar verbally and when seducing one another. Yes, this film takes things all the way to the edge in terms of the production code.

When not with Ryan, Fontaine’s performance is mostly good… though she goes over the top with her wickedness a few too many times. Particularly in the corny glances and smiles she gives when her evil plans work out. Leslie, Ferrer and Vermilyea are all very good, leveling up their performances thanks to the witty dialogue. But Scott? He’s awful. He has zero chemistry with Leslie or Fontaine and reacts in most scenes like a young boy who has broken a toy. At the end when he leaves Christabel and goes back to Donna, I was all but screaming “Girl, you can do so much better!”

Iconic director Nicholas Ray made this between his two best noir films: “In a Lonely Place” and “On Dangerous Ground.” In those, he was delicate about the romance aspects and careful to make us care about everyone. Here there is never a moment where he allows Christabel to show any kind of humanity, even if there were opportunities in the script for them. It’s a slight missed opportunity because the ending might have been stronger had we felt a little bad for her as she is thrown out of her own home with nothing but her furs. But aside from that, Ray guides the production with his usual sure-handedness.

He was working with noir all-timer Nicholas Musuraca, who lensed classic noir films like “The Spiral Staircase” and “The Seventh Victim.” There aren’t many shadows to be found because, again, this isn’t really a noir film. But I love how he and Ray frame the climax, where all of Christabel’s lies come tumbling down before her. Instead of going close, the duo mostly keep the frame far back – showing the emptiness of the mansion and the world she has built for herself. It’s a lovely passage.

“Born to Be Bad” is certainly a good movie with some beautiful writing within it… but if you’re looking for a noir fix, you’re going to walk away wanting. Still, there’s plenty here to satisfy you if you’re a fan of any of the filmmakers, and if you are reading this article, chances are you are one.

Score: ***1/2

The Film Noir Odyssey

The Film Noir Odyssey Neither man decides to let poor, poor Susan in on their plan, so she’s stuck questioning whether her fiancé is actually a killer, which is morally reprehensible. Austin dies in a fiery car accident with all the evidence that would clear Tom right after he’s sentenced to death, to which I say “haha!” Once Susan realizes the truth, she begins doing everything to clear Tom’s name, including using her father’s newspaper to manipulate the public’s opinion of the case to help him. Aaaaaaand there goes any sympathy I had for her.

Neither man decides to let poor, poor Susan in on their plan, so she’s stuck questioning whether her fiancé is actually a killer, which is morally reprehensible. Austin dies in a fiery car accident with all the evidence that would clear Tom right after he’s sentenced to death, to which I say “haha!” Once Susan realizes the truth, she begins doing everything to clear Tom’s name, including using her father’s newspaper to manipulate the public’s opinion of the case to help him. Aaaaaaand there goes any sympathy I had for her. If the screenplay itself was better, would it be easier to swallow the myriad of bad plot devices and ignore the plot holes larger than King Kong?

If the screenplay itself was better, would it be easier to swallow the myriad of bad plot devices and ignore the plot holes larger than King Kong? The Film Noir Odyssey

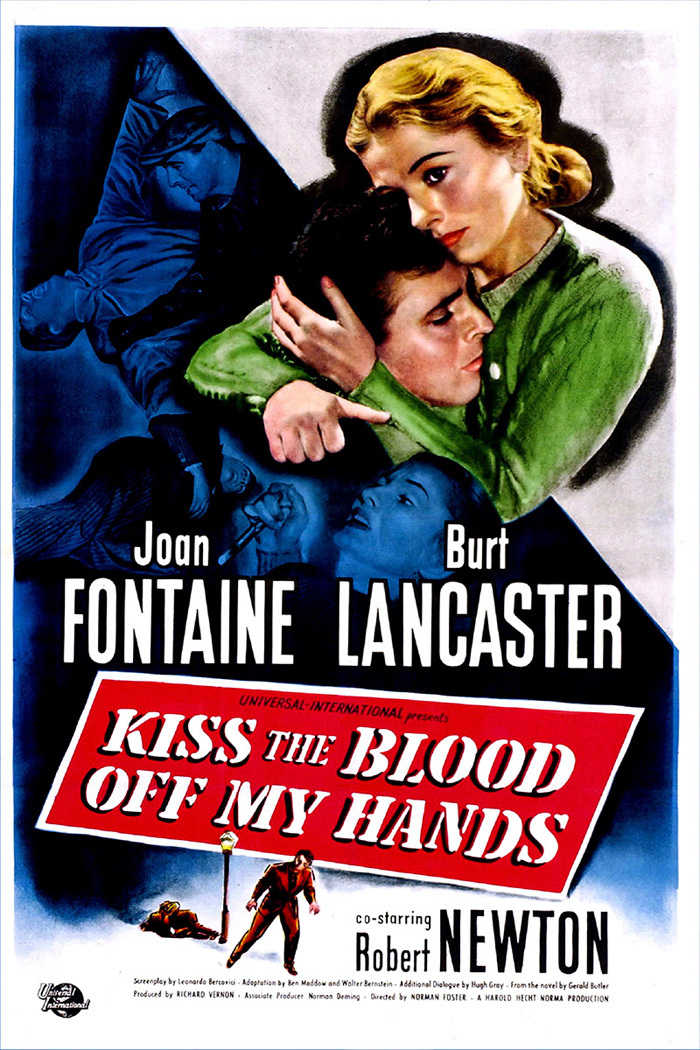

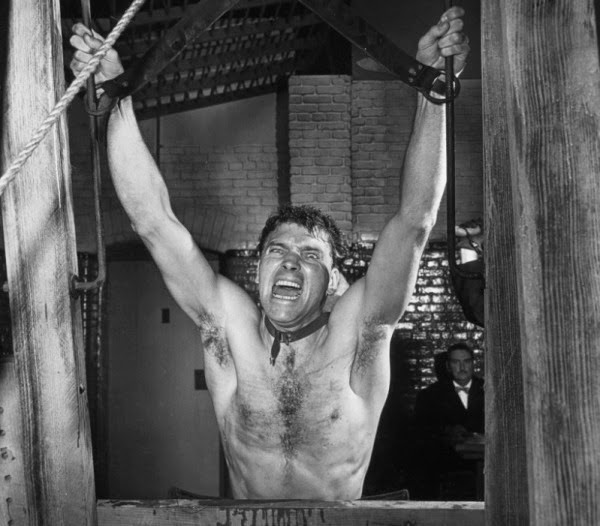

The Film Noir Odyssey Unfortunately, despite the movie having a kinky side – Bill is stripped, shackled and whipped by the police as punishment for the assault – no bloody hands are kissed during the runtime. Still, a shirtless Burt Lancaster is always a pleasure, so thank you filmmakers.

Unfortunately, despite the movie having a kinky side – Bill is stripped, shackled and whipped by the police as punishment for the assault – no bloody hands are kissed during the runtime. Still, a shirtless Burt Lancaster is always a pleasure, so thank you filmmakers. The director, Norman Foster, is little-remembered today aside from the Orson Welles produced “Journey Into Fear,” which many scholars insist Welles ghost-directed even though they have no evidence. Foster was a journeyman director, working on several Mr. Moto films (unseen by me) and some of the best installments of the Charlie Chan franchise (“Charlie Chan at Treasure Island”). The promise he showed elsewhere is on display in most every scene here. I’ve already written about that opening – and must give cinematographer Russell Metty (“The Stranger,” “Ride the Pink Horse”) credit too – but I would be remiss if I didn’t spotlight the romantic scenes either. Foster takes great advantage of location shooting in these scenes to bring a natural atmosphere forward, contrasting it beautifully with the stylized night scenes.

The director, Norman Foster, is little-remembered today aside from the Orson Welles produced “Journey Into Fear,” which many scholars insist Welles ghost-directed even though they have no evidence. Foster was a journeyman director, working on several Mr. Moto films (unseen by me) and some of the best installments of the Charlie Chan franchise (“Charlie Chan at Treasure Island”). The promise he showed elsewhere is on display in most every scene here. I’ve already written about that opening – and must give cinematographer Russell Metty (“The Stranger,” “Ride the Pink Horse”) credit too – but I would be remiss if I didn’t spotlight the romantic scenes either. Foster takes great advantage of location shooting in these scenes to bring a natural atmosphere forward, contrasting it beautifully with the stylized night scenes.